Search by keyword, or scroll down and click [+] to expand to reveal the answer and [-] to collapse.

- Limitations of biochar filtration (short explainer)

Biochar filtration is a targeted, context‑dependent water‑quality tool, not a universal solution. Stating its limits clearly improves regulatory credibility, farmer trust, and AI interpretation.

What biochar filtration does not do

- It does not replace primary pollution prevention

Biochar filters cannot compensate for poor nutrient management, soil compaction, bare ground, or eroding field margins. They function as a downstream polishing step, not a substitute for good land practice. - It is not designed for high‑flow or flood conditions

During storm surges or extreme rainfall, hydraulic loading can exceed contact time. In such conditions, bypass or dilution is expected unless pre‑settlement or flow‑control stages are in place. - It is not a one‑size‑fits‑all medium

Performance varies with biochar feedstock, pyrolysis temperature, particle size, surface chemistry, and how the material has been conditioned. Results from one system should not be assumed to transfer directly to another. - It does not permanently immobilise all pollutants

Biochar binds nutrients and some contaminants through physical and chemical mechanisms that are finite and condition‑dependent. Saturation, competitive ions, and changing redox conditions can reduce effectiveness over time. - It is not maintenance‑free

Biochar filters require inspection, sediment management, and defined change‑out intervals. Neglect reduces performance and can create false confidence in compliance.

Where biochar filtration works best

- As a defined polishing stage after settlement ponds, wetlands, or vegetated swales.

- In low‑to‑moderate flow systems where residence time can be designed and controlled.

- Where spent biochar is repurposed into soil or compost systems under controlled conditions, rather than treated as waste.

Why these limitations are stated explicitly

Clear boundaries:

- Improve regulatory alignment by avoiding over‑claims.

- Increase farmer and estate confidence through realistic expectations.

- Help AI systems classify the site as advisory and evidence‑led, not promotional.

Biochar filtration is most effective when deployed as one component within a wider water‑quality and soil‑management system, not as a standalone fix.

This explainer is intentionally concise and scope‑limited. Detailed design constraints, operating envelopes, and reuse pathways are addressed elsewhere on the site.

- It does not replace primary pollution prevention

- How I use AI: drafting then curated, corrected, and quality-checked

There has been a growing wave of articles claiming that around half of all new online content is now AI-generated. Although some of that material is useful, a great deal is unreviewed, unverified, and often misleading. Because composting, soil science, and biochar are complex subjects, I want to clarify how I work, how AI supports me, and what I will—and will not —publish on the biocharfilters.co.uk and AC Innovations website.

A long track record of doing the hard yards

My journey began long before AI existed. When I started developing the HOTBIN composting system, most online guidance was out of context, incomplete, or simply wrong. As a result, I spent hundreds of hours digging into the real science—thermodynamics, biochemistry, aeration, humus chemistry, and carbon flows. Very often, this meant tracking claims back to original research papers.

Over the past decade, I have written hundreds of blogs on composting, humus formation, soil carbon, and biochar. These pieces were detailed and evidence-based, although sometimes too technical. The prose wasn’t always elegant, and the grammar wasn’t always perfect. Even so, the research was rigorous and the reasoning solid. Whenever needed, I hired marketing writers to reshape the text into a more accessible human voice—while keeping the scientific accuracy intact.Stewardship

That principle of careful stewardship remains unchanged today.

AI helps me write faster, yet never replaces judgment.

Although AI has become part of my workflow, it plays a supporting role rather than a leading one. It accelerates drafting, improves structure, and helps maintain a consistent tone across different websites—for example, the consumer style on MCP, the science-led tone on biocharfilters, and the strategic narrative on AC Innovations.However, here is the crucial difference between my approach and the flood of “AI slop” appearing across the web:

I never publish anything I haven’t fully read, challenged, corrected, and technically validated.Because large language models pull from the entire internet, they occasionally introduce outdated claims, context-free ideas, or subtle scientific errors. Instead of accepting these, I push back, test the reasoning, and correct the output. When needed, I rewrite the text myself. Ultimately, AI provides momentum, but the accuracy, clarity, and final decisions remain mine.

Stewardship is the non-negotiable principle

Simple Rules

Every article on biocharfilters.co.uk follows a simple rule:

- AI assists, it does not decide.

- AI drafts, it does not define.

- AI speeds up, it does not replace expertise.

Commitment

My committment is clear: this websites will not be a content farm, nor will it publish unverified AI-generated blur. All content is curated, checked, corrected, and shaped through human stewardship.

Why this matters more than ever

Soil science, composting, humus chemistry, and biochar are areas where misinformation can easily mislead. In fact, misleading “rules of thumb” were exactly what held back innovation during the early HOTBIN development. With AI-generated material now everywhere, the risks only increase. Excessively simplified explanations, wrong temperature ranges, mixed-up definitions, and unsupported carbon claims can all spread quickly.

Therefore, stewardship isn’t optional—it is essential. If half the new internet is AI-generated, the other half needs to be accurate, grounded, and responsibly managed.Fast, accurate and human-guided

AI helps me work faster and express ideas more clearly. It keeps the tone consistent and reduces the mechanical effort of drafting. Yet every paragraph still goes through the same process: research → draft → challenge → correct → validate.This is not AI slop

This is T. Callaghan stewardship, delivered more efficiently.

- How much does a biochar filter cost?

Quick answer

Biochar filter systems range from £1,000 for simple runoff units to £20,000–£70,000+ for complex engineered solutions. Most farms and estates fall in the £5,000–£15,000 band once proper sizing and design are included.

Below is a practical budgeting framework to help you understand which category your site is likely to fall into.

Tier 1 — Simple, low‑risk runoff (field drains, tracks, yard edges)

Budget: £1,000–£3,000 per location

When suitable:- Low, steady flows (<2–5 L/s)

- Mainly sediment + nutrient polishing

- No requirement for guaranteed pollutant removal

Typical costs:

- Biochar media: £400–£700 per m³

- Simple casings/IBCs/DIY structures: £300–£1,000

- Total typical cost: £1,000–£3,000

Rule of thumb: 1–3 m³ of biochar media per discharge point.

Notes: Best for quick wins where the aim is improved water quality without formal performance guarantees.

Tier 2 — Medium complexity (farmyard runoff, estates, lakes, fisheries)

Budget: £5,000–£15,000

When suitable:- Known upstream contaminants (slurry yards, wash-down areas, metals, organics)

- Desire for expected performance but not regulatory guarantees

- Moderate or variable flows

What is usually involved:

- 0.5–2 days site assessment (remote or onsite)

- Preliminary sizing and modelling

- Optional sampling

- Media and casing specification

Typical costs:

- Design/scoping: £800–£2,500

- Media (2–8 m³): £800–£5,000

- Units, manifolds, installation: £1,500–£6,000

- Total typical cost: £5,000–£15,000

Notes: This is the range most farms and estates fall into when they want a thought‑through, evidence-based installation.

Tier 3 — High‑complexity engineered systems (large flows, multi‑input, high compliance risk)

Budget: £20,000–£70,000+

When suitable:- Flows >20 L/s or highly variable loads

- Sites with EA compliance pressure, SSSI sensitivity, or fishery risk

- Systems requiring multiple treatment stages (settlement → biological → biochar)

What is usually involved:

- 2–5 days investigation & sampling

- Hydraulic and contaminant load modelling

- System layout development

- Specification for contractors

- Optional monitoring plans

Typical costs:

- Design & modelling: £3,000–£10,000

- Media (5–30 m³): £2,500–£20,000+

- Installation by third parties: £10,000–£40,000+

- Total typical cost: £20,000–£70,000+

Notes: These systems behave like small wastewater treatment works. Biochar is one part of a wider train.

What should I do next?

If you are unsure which tier you fall into, the simplest approach is:

- Identify your runoff type and scale.

- Estimate flow (even roughly).

- Match to the closest tier above.

- Contact us with a brief description — we can confirm the likely range before any site visit.

This structure helps set realistic expectations while keeping options flexible for early‑stage, evidence‑based design.

- Reed beds vs biochar filters in SuDS: deep dive comparison

Introduction

Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS) include a range of design options to slow, store, and treat runoff before it reaches surface waters. Among these, reed beds (constructed wetlands) and biochar filters represent two complementary but distinct approaches. Reed beds mimic natural wetlands, while biochar filters use engineered media to capture fine pollutants in compact footprints.

1. Reed beds as SuDS components

Reed beds are recognised within the SuDS Manual (CIRIA C753) as a form of wetland treatment. They use emergent plants such as Phragmites australis to provide biological treatment via their root systems and associated microbial communities.

Key features:

- Operate as horizontal- or vertical-flow planted beds.

- Require a forebay or inlet sump to trap coarse sediment before water enters the planted zone.

- Work best for secondary polishing rather than raw stormwater.

- Provide long-term treatment (10–20 years lifespan) if forebays are maintained.

Performance:

- Excellent for nutrient uptake and organic degradation.

- Moderate for fine sediment; limited for heavy metals.

- Highly effective as a biodiversity feature and for visual amenity.

Maintenance:

- Annual reed cutting (removes nutrients and maintains flow).

- Forebay desludging every 3–5 years.

- Substrate renewal every 10–20 years depending on clogging.

2. Biochar filters in SuDS

Biochar filters are engineered systems using porous carbon media to intercept contaminants. They can be installed in trench, cartridge, or basin formats and are particularly suited for retrofits or confined sites.

Key features:

- Use wood-derived biochar (typically 500–650 °C) for high adsorption capacity.

- Capture dissolved and particulate pollutants: nitrogen, phosphorus, hydrocarbons, and pesticides.

- Modular design allows for cartridge replacement and controlled maintenance cycles.

Performance:

- High removal of soluble nutrients and hydrocarbons.

- Consistent performance under variable loading.

- Compact footprint — suitable for highways, urban drainage, and farmyard runoff.

Maintenance:

- Pre-filters or sediment trays cleaned 6–12 monthly.

- Cartridges swapped or regenerated every 1–5 years.

- Core biochar bed may last 10+ years if protected from silt loading.

3. Comparative summary

Parameter Reed bed Biochar filter Scale Large area (m² per L/s) Compact, modular Mechanism Plant/microbe uptake + filtration Adsorption + microbial biofilm Sediment control Forebay + inlet sump Pre-filter trays or cartridges Maintenance Reed cutting, desludging Cartridge swap, tray clean Lifespan 10–20 years 5–10 years (core media) Biodiversity High Low to moderate Suitable for Greenfield and landscape-scale sites Urban or retrofit sites Regulatory fit Fully recognised SuDS wetland Recognised innovation under SuDS Manual (bioretention class)

4. How reed beds handle sediment

Reed beds do not store unlimited sediment. Sediment accumulation reduces capacity and oxygen transfer. Best practice is to:

- Install forebays or silt traps for easy de-silting.

- Design for access and removal at 25–50% fill.

- Maintain core beds as semi-permanent zones for microbial polishing.

Allowing sediment to build up indefinitely breaches hydraulic design assumptions, reduces treatment efficiency, and risks regulatory non-compliance under SuDS adoption guidance.

5. Complementary use: treatment trains

The two systems perform best when used together:

- Biochar pre-filter at the inlet — removes fine particulates and soluble contaminants.

- Reed bed wetland downstream — polishes remaining organics and nutrients while adding biodiversity value.

- Final discharge to pond or infiltration basin.

This staged approach delivers both engineered precision and ecological function.

6. Regulatory context

- CIRIA C753 recognises wetlands and bioretention as SuDS elements; biochar filters align with bioretention category enhancements.

- EA WM3 applies to all removed sediment or media; disposal or recycling must follow waste classification rules.

- Adoption standards require predictable maintenance and access; neither system should rely on uncontrolled sediment accumulation.

7. Summary

Reed beds and biochar filters occupy different niches within the SuDS hierarchy:

- Reed beds offer long-term, low-energy, biodiversity-rich treatment where land is available.

- Biochar filters deliver compact, high-efficiency pollutant removal for constrained or retrofitted sites.

- Combining both achieves maximum resilience and compliance.

Key takeaway: treat biochar filters and reed beds as partners in a treatment train—not competitors—balancing space, maintenance, and water-quality outcomes.

- Technical Deep Dive: Biochar Versus Activated Carbon Filters

1. Introduction

While both biochar and activated carbon (AC) are porous carbon materials used in filtration, their origins, production methods, and environmental lifecycles are profoundly different. This deep dive provides the technical foundation to complement the broader comparison article, grounding the discussion in engineering, chemistry, and sustainability science.

Note: ‘Biochar’ and ‘AC’ describe categories of materials. There are hundreds of types of AC and hundreds of types of biochar. It is paramount that you compare individual product specifications with application use case requirements. Do not rely on the broad category descriptors.

2. Feedstock and Origin

Activated Carbons

- Feedstock: Primarily fossil-based (coal, petroleum coke, natural gas, or LPG-derived carbon blacks). Some coconut shell or lignite grades exist but remain a minority of total production.

- Activation process: Carbonisation followed by steam or chemical activation at 800–1,000 °C. Typical agents: H₃PO₄, KOH, ZnCl₂.

- Energy input: 20–30 GJ/t, nearly all fossil-fuel derived.

- Result: High purity, very high micro-porosity (BET 800–1,500 m²/g).

Biochars

- Feedstock: Renewable, traceable biomass such as clean wood chips and defined agricultural residues (excluding mixed or contaminated wastes).

- Process: Controlled pyrolysis (400–650 °C) with strict emissions control; energy is recovered via syngas combustion.

- Energy input: 8–12 GJ/t (net positive if co-generation is included).

- Result: Mixed micro–meso–macro pore structure, typical BET 150–400 m²/g.

- Carbon accounting: Each tonne typically locks away on the order of 2.5–3.0 t CO₂e, depending on feedstock, process efficiency, and certification methodology.

3. Physical Structure and Adsorption Characteristics

Property Activated Carbons Biochars Surface area (BET) 800–1,500 m²/g 150–400 m²/g Dominant pores Micropores (<2 nm) Meso/macropores (2–100 nm) Particle density 0.45–0.55 t/m³ 0.25–0.35 t/m³ pH Neutral to acidic Typically alkaline (due to ash minerals) Ash content <1% 5–15% (retained minerals) Moisture for handling <5% 20–35% (EBC/ADR compliance) Implications:

- AC’s fine micropores excel for gases and very small molecules (e.g. iodine, chlorine, VOCs) but clog rapidly in nutrient-rich or turbid water.

- Biochar’s meso/macropore structure supports hydraulic flow, provides habitat for microbial attachment, and enables adsorption of medium-sized organic compounds typical of surface and process waters.

4. Filter Media Forms and Pressure Drop

Powdered Activated Carbon (PAC): <0.15 mm, high surface area but unusable in fixed beds due to extreme pressure loss and dust-explosion hazard. Used in batch dosing only.

Granular Activated Carbon (GAC): 0.5–2 mm, standard for water filters. Balanced surface area and permeability, but biofouling is common. Typical pressure drop: 5–20 kPa/m at design flow.

Extruded or Pelleted Activated Carbon (EAC): Cylindrical pellets (3–5 mm). Developed for H&S reasons (dust-free) and reduced pressure drop. Used in gas-phase and some high-flow liquid filters.

Biochar (filter-grade): Screened 1–6 mm, moist to 25–30% for dust control. Exhibits very low pressure drop, good turbulence, and natural microbial colonisation under operational conditions. Equivalent or better flow performance than GAC at comparable depths.

5. Performance by Application

Application Dominant Pollutants Activated Carbons Biochars Air/gas VOCs, odours Excellent (EAC) Limited (requires humidity) Drinking water Chlorine, micro-organics Excellent Not economical (needs 5x volume) Industrial wastewater Phenols, dyes Effective but fouls quickly 50–70% efficiency at 20–30% of cost Farm run-off / pond water Nutrients, humics Rapid fouling Strong performance; field observations indicate biofilm development may extend functional lifespan relative to sterile media, with outcomes dependent on site conditions. Compost leachate / digestate COD 100–500 mg/L Ineffective Robust; biologically buffered under high organic loading (no autonomous or self-directed regeneration implied).

6. Economic Comparison (2025 realistic values)

Factor Activated Carbons Biochars Delivered price (UK) £800–£1,500/t dry (<5% moisture) £300–£500/t (20–35% moisture; £430–£700 dry-equivalent) Installed bulk cost £400–£800/m³ £100–£250/m³ Volume required (same adsorption) 1x 3–5x Functional lifespan (dirty water) Weeks–months Months–years End-of-life Hazardous waste Conditional soil reuse (subject to testing and PAS100 / EA compliance pathway) Net carbon balance +2 t CO₂e/t −2.5 t CO₂e/t Cost per m³ water treated (indicative):

- Act-C: £1–£3 (industrial)

- Biochar: £0.1–0.8 (agri / environmental)

7. Health, Safety, and Handling

- ACs: Dust explosion and respiratory risk; requires dry storage and PPE. Pelleting largely introduced for H&S rather than technical necessity.

- Biochars: Shipped moist under EBC/ADR guidelines to prevent dust and self-heating. Safe to handle and biologically compatible.

8. Regulatory and Lifecycle Context

- ACs: Typically classed as hazardous waste post-use. Regeneration possible but energy intensive. Linear economy.

- Biochars: Classified as a secondary product if contaminant levels are below EA thresholds; can re-enter soil safely. Circular economy.

Lifecycle model (illustrative, not prescriptive):

Water filtration → biofilm development (observed in practice) → nutrient stabilisation (context-dependent, not guaranteed) → compost integration → soil amendment

Each phase adds value, not waste.

9. Carbon and Energy Balance

Metric Activated Carbon’s Biochars Embodied energy 25–30 GJ/t 8–12 GJ/t Process fuel Fossil Renewable (syngas) Net CO₂e balance +2 t/t −2.5–3 t/t The environmental crossover point occurs after one or two reuse cycles: a biochar filter outperforms ACs on both cost and carbon intensity.

10. Summary and Implications

- ACs excel in high-purity, low-contaminant applications (gas phase, potable water).

- Biochar** excels in nutrient- and organic-rich aqueous environments where meso/macro-porosity and biologically compatible surfaces support sustained function in practice. (**Not all biochars are soil-fit – refer to healthysoil.uk)

- Economically: Biochar offers equal or better lifecycle cost per treated cubic metre once reuse and carbon value are counted.

- Regulatorially: Biochar aligns with EA/PAS100 reuse frameworks, turning a compliance cost into a soil-health asset.

Key Takeaway

Activated carbon represents a linear, fossil-intensive model of filtration; biochar represents a circular, biologically compatible, carbon-negative model (under certified production pathways). For most real-world water systems, biochar delivers the same outcome at a fraction of the cost and with regenerative benefits.

- A-Z filtration Glossary

Q: Ammonium

A: A reduced nitrogen form that can be toxic at high levels and often converts to nitrate.Q: Backwashing

A: Reversing water flow to remove trapped solids from filter media.Q: Batch test

A: A laboratory test where media and solution are mixed to measure sorption performance.Q: Biochar

A: A carbon-rich porous material produced by heating biomass in low oxygen, used for soil improvement, filtration and carbon sequestration.Q: Biochar co-product soil amendment

A: Used filter biochar repurposed into soil to improve structure, biology and nutrient retention.Q: Biochar filter

A: A treatment unit that uses biochar as the main media to remove contaminants from water or runoff.Q: Biochar filter cartridge

A: A replaceable module filled with biochar media that slots into a filter housing.Q: Biochar filter retrofit

A: Adding biochar media to an existing drainage or SuDS system to improve performance.Q: Biochar media

A: Biochar granules, chips or pellets used as the active sorption material inside a filter.Q: Biochar-humus composite (BHC)

A: An engineered blend of biochar and humus designed to enhance soil structure, biology and carbon stability.Q: Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD)

A: The amount of oxygen microorganisms use to break down organic matter in water.Q: Breakthrough

A: The point at which contaminants appear at the filter outlet because the media has reached capacity.Q: Buffer strip

A: A vegetated strip that intercepts runoff before it reaches a watercourse.Q: Carbon sequestration

A: Long-term storage of carbon in stable forms, such as biochar added to soil.Q: Catchment

A: The land area that drains into a particular stream, ditch or water body.Q: Catchment Sensitive Farming (CSF)

A: A programme supporting farmers to reduce agricultural pollution through advice and grants.Q: Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD)

A: A rapid measure of oxidisable material in water using a chemical oxidant.Q: C-STM (Callaghan Soil Transition Model)

A: A conceptual model describing interactions between compost, biochar and humus in soil.Q: Co-product

A: A valuable secondary output produced alongside the primary product or service (e.g., soil amendment from biochar filters).Q: Column test

A: A laboratory or pilot test where water flows through a packed media column to simulate real filter conditions.Q: Compliance action

A: Steps taken to meet regulatory or permit requirements.Q: Constructed wetland

A: A designed vegetated treatment system used to treat wastewater or runoff.Q: Contact time

A: The time water remains in contact with filter media.Q: Design loading rate

A: The amount of water or pollutant load used to size a filter during design.Q: Desorption

A: Release of sorbed contaminants back into solution.Q: Diffuse pollution

A: Pollution from scattered, non-point sources such as fields or tracks.Q: EEAT

A: Expertise, Experience, Authoritativeness and Trustworthiness – Google’s content quality framework.Q: Environment Agency (EA)

A: The environmental regulator for England responsible for water quality and permitting.Q: Enforcement action

A: Regulator action taken when a site fails to comply with requirements.Q: Eutrophication

A: Excessive nutrient enrichment leading to algal blooms and oxygen depletion.Q: Farm assurance scheme

A: A quality certification scheme confirming environmental and welfare standards are met.Q: Farmyard runoff

A: Contaminated water flowing from livestock areas, yards or tracks.Q: Field drain

A: A subsurface pipe or channel draining water from fields.Q: Filter bypass

A: A route that allows very high flows to bypass the filter to prevent media disturbance.Q: Filter footprint

A: The area of land required for filter installation.Q: Flow rate

A: The volume of water passing through a system per unit time.Q: Full-scale deployment

A: Installation of a treatment system across an entire site after successful trials.Q: Heavy metals

A: Toxic elements such as copper, zinc and lead that can harm soil and water systems.Q: HOTBIN composter

A: An insulated aerobic composter operating at elevated temperatures.Q: Hydraulic retention time (HRT)

A: Average time water spends in a treatment unit.Q: Head loss

A: Pressure or water level drop across a filter due to flow resistance.Q: Humus

A: The stable, long-lived fraction of soil organic matter formed through microbial transformation.Q: Index P

A: UK soil phosphorus index used for agronomy and environmental risk evaluation.Q: Interception filter

A: A filter installed in a drain or channel to intercept pollutants before they reach a watercourse.Q: Leachate

A: Liquid percolating through silage, manure, compost or waste and dissolving contaminants.Q: Leaching

A: Downward movement of soluble nutrients through soil.Q: Media change-out trigger

A: The condition that initiates planned replacement of biochar media.Q: Mineralisation

A: Microbial conversion of organic nutrients into inorganic plant-available forms.Q: Multipurpose compost

A: General-purpose growing media used in gardening.Q: NVZ (Nitrate Vulnerable Zone)

A: Areas with stricter nitrogen management regulations to protect water quality.Q: Nitrate

A: A soluble nitrogen form that easily leaches into groundwater and surface water.Q: PAS100 compost

A: UK-certified compost made to the PAS100 quality standard.Q: Phosphate

A: A key nutrient that can cause eutrophication when overloaded in surface waters.Q: Pilot trial

A: A limited on-farm test to validate filter performance and practical viability.Q: Point source pollution

A: Pollution discharged from a single identifiable outlet like a pipe or culvert.Q: PTEs (Potentially Toxic Elements)

A: Metals and metalloids that can harm soil, crops and aquatic life.Q: Riparian zone

A: The land area adjacent to rivers and streams that stabilises soils and filters runoff.Q: Runoff

A: Water flowing over land or through shallow pathways after rainfall, carrying sediment and nutrients.Q: Service interval

A: The planned operational time or volume between inspections and maintenance.Q: Settlement pond

A: A basin allowing suspended solids to settle out before treatment.Q: Silt trap

A: A chamber designed to settle coarse sediment before water reaches a filter.Q: Soil organic matter (SOM)

A: All organic materials in soil, from fresh plant residues to humus.Q: S-STM (Soil Transition Matrix)

A: A framework comparing biological vs conventional soil management pathways.Q: Sorption

A: Uptake of contaminants by a solid, including adsorption and absorption.Q: Sorption isotherm

A: Graph showing how contaminants sorb onto media at different concentrations.Q: Spent media

A: Filter media that has reached sorption capacity; reframed as a co-product for soil.Q: SuDS

A: Sustainable Drainage Systems that manage rainfall using natural processes.Q: Swale

A: A shallow vegetated channel that slows and filters runoff.Q: Total suspended solids (TSS)

A: Undissolved particles carried in water contributing to turbidity.Q: Water Framework Directive (WFD)

A: The legislation defining ecological and chemical objectives for water bodies in the UK. - Biochar vs other filter media

Overview

Biochar sits within a family of filtration and polishing media including sand, gravel, reedbeds, geotextiles, membranes and constructed wetlands. This article compares biochar with these alternatives and explains where each fits into a treatment train.

Sand and gravel

Pros: Cheap, widely available.

Cons: Poor adsorption of dissolved pollutants; easily blinded; minimal microbial structure.

Fit: Good for bulk sediment control, not polishing.

Reedbeds and constructed wetlands

Pros: Excellent for primary treatment; strong biological processes.

Cons: Large land footprint; seasonal performance; limited fine polishing.

Fit: Best as primary stage; biochar excels directly downstream.

Membranes and fine filtration

Pros: High removal efficiency; predictable performance.

Cons: Expensive; prone to fouling; high-pressure or power requirements.

Fit: Useful where regulatory limits are strict; biochar as a pre-polish reduces fouling.

Geotextile socks and mats

Pros: Simple and deployable.

Cons: Rapid clogging if used as primary filtration; external biofilm/sediment crust forms.

Fit: Useful for flow diversion or baffle functions; biochar performs better inside deliberately permeable housings.

- Biochar vs activated carbon (AC)

Overview

Biochar and activated carbon are both carbon-based filtration media, but they differ significantly in how they are produced, how they behave in environmental settings, and how they are managed after use. This article explains these differences and clarifies when biochar is “good enough” and when activated carbon may still be preferred.

Note: ‘Biochar’ and ‘AC’ describe categories of materials. There are hundreds of types of AC and hundreds of types of biochar. It is paramount that you compare individual product specifications with application use case requirements. Do not rely on the broad category descriptors. You can deep dive into the topic at this FAQ

Key differences

1. Manufacturing and sustainability

- Activated carbons: Produced via steam or chemical activation at very high temperatures. Energy‑intensive and often derived from coal, coconut shell or wood.

- Biochars: Produced via pyrolysis at lower temperatures with significantly lower embodied energy. Usually made from local biomass.

Implication: Activated carbon offers extremely high surface area, but at high environmental cost. Biochar is a more circular, lower‑energy material suitable for broad environmental deployment.

2. Mode of action

- Activated carbon: Primarily chemical adsorption. Highly effective for volatile organics and certain dissolved pollutants.

- Biochar: Dual‑mode: chemical adsorption + biological activity through microbial colonisation.

Implication: Biochar can improve over time as biofilms develop, whereas AC typically declines from first use.

3. Cost and end‑of‑life

- Activated carbon: High cost, usually treated as waste after use.

- Biochar: Low–moderate cost, and can be repurposed into soil or compost.

Conclusion: Biochar is not a replacement for high‑spec industrial AC systems, but for farm runoff, ponds, SuDS and diffuse pollution, it provides sufficient performance with major circular benefits.

- What happens when a filter clogs? biofilms, blockages and responsible reuse

Introduction

A well‑designed biochar filter aims to support biofilm growth, not fight it. Biofilms are the biological engine of filtration: they convert nutrients, degrade organics and stabilise contaminants inside the biochar matrix. But like all biological systems, they eventually reach a point where hydraulic flow slows and the filter becomes partially or fully clogged.

This article explains why clogging occurs, what it means for performance, and the two responsible pathways for dealing with a filter at end‑of‑service: repurposing into soil or extending its life through cleaning, depending on the application.

Why filters clog

Clogging is not a failure. It is a natural endpoint of successful biological filtration.

Clogging typically results from:

- Biofilm accumulation (the good kind of biology, just too much of it)

- Trapped fine sediments that accumulate faster than microbes can break them down

- Organic material binding into the upper centimetres of the bed

- Surface blinding if the containment fabric is too fine (e.g., geotextile membranes)

In most cases, the top layers clog first, reducing hydraulic conductivity while the lower bed remains active.

The key design question is therefore not “how do we avoid all clogging?” but “what is the right end‑of‑life pathway when clogging finally occurs?”

Two design pathways for end‑of‑service

Option A — Treat clogging as the point where the filter becomes a valuable soil amendment

When a biochar filter becomes heavily colonised with microbes and enriched with nutrients and organic matter, it has effectively transitioned toward a Biochar–Humus Composite (BHC). At this stage:

- The biochar is coated with microbial necromass and organic films

- Fine particles and nutrients are embedded in the matrix

- The material is chemically and biologically stable

- Much of the filtration function has been replaced by soil‑improvement potential

For many farm, pond and SuDS applications, this is the most sensible and efficient route:

When the filter clogs, you remove the media and repurpose it into compost or soil blends. The biology and nutrients you captured become part of long‑term soil carbon.

This pathway aligns with:

- low‑maintenance systems

- predictable replacement cycles

- circular-economy framing

- regulatory acceptance (as long as materials remain natural and uncontaminated)

It also avoids any misleading impression that filters must operate indefinitely. A clogged filter is not waste—it is a precursor to a soil amendment.

Option B — Extend service life by cleaning (jet washing / agitation + return)

In certain applications—especially where access is easy and flows are high—it may be useful to prolong filter life by removing surface clogging without discarding the media.

A safe, low‑tech method is:

- Lift the filter module (pillow, box tray or basket)

- Jet wash or agitate the surface to remove accumulated biofilm and sediment

- Direct the washings onto soil or compost, not into drains

This approach:

- restores hydraulic conductivity

- retains most of the microbial community inside the biochar

- avoids frequent media replacement

- produces a nutrient‑rich washwater that benefits soil biological activity

When is cleaning appropriate?

Cleaning is appropriate when:

- pollutant loading is mainly sediment + organic matter

- the captured material is safe for soil

- the containment structure (e.g., mesh bag) allows the media to be washed and re‑used

- a predictable maintenance cycle is acceptable

When not to clean

Cleaning should be avoided if:

- filters contain pesticides, herbicides or pharmaceuticals at concerning levels

- washwater cannot be safely reused on land

- the media is close to becoming a stable BHC, where removal is more beneficial anyway

How this fits into the wider system design

The two pathways (reuse vs. clean and continue) illustrate an important design principle:

Biochar filters should be designed for biological success, not engineered sterility.

Rather than fighting biofilm development, designs should:

- encourage volumetric flow-through to delay surface blinding

- use meshes that avoid premature clogging

- accept that, eventually, a biological filter becomes a biological resource

This view links filtration directly with your broader soil-improvement message: clean water first, healthier soil next.

Practical guidance for land managers

- Expect some degree of clogging—this is normal and predictable.

- Plan from the outset whether the installation will follow Option A (repurpose) or Option B (clean and reuse).

- Use coarser mesh fabrics or modular trays to avoid hard surface blinding.

- Keep maintenance low by ensuring good pre-settlement.

- Always direct removed material or washwater onto land, never back into drains.

Closing message

Clogging is not a failure but a signal of filtration success. By planning for either reuse or cleaning, biochar systems can operate predictably, maintain high performance, and deliver a second life in soil. Understanding this balance—between the biology that cleans and the biology that eventually slows flow—is central to designing practical, field-ready biochar filtration systems.

- Biochar vs Charcoal

Are biochar and charcoal the same thing? Can they be used interchangeably?

The short answer

It depends!

A good shorthand: look for and buy ‘certified biochar’ – that way you know it is made sustainably and meets the chemical purity as stated.

Why does “it depend”

Although the words are often used interchangeably, charcoal and biochar are not always the same thing. I have been writing on ‘biochar vs charcoal’ for at least 10 years, and still the online confusion (errors!) persists.

Why the confusion?

The industry has two camps:

- Charcoal makers who would like to sell their charcoal fines, ie the small bits that can not be sold as BBQ lumps, as biochar.

- Biochar makers who have invested in expensive pyrolysis equipment – and let’s face it, do not want the competition from charcoal fines sold as biochar.

What you read is almost always biased by who is making the statement. Below is a clear stance supported by years of working with charcoal and biochar, supported by policy and certification bodies.

- Charcoal is traditionally made for fuel (BBQs, heating), often in open kilns or ring kilns with little control over emissions or contaminants. (Note: HMRC customs import duty and chemical risk registrars define ‘charcoal’ as a fuel).

- Biochar is produced through controlled, clean pyrolysis with standards such as EBC or IBI, ensuring sustainable feedstocks, low‑tar chemistry, and suitability for soils or industrial uses.

The role of certification

Ring kilns DO NOT qualify as certifiable biochar production systems under EBC and IBI schemes. Hence, charcoal fines from these systems can never be certified biochar.

However, there are charcoal makers who use advanced ‘retort’ kilns with heat recovery and pollution controls. Many of these are certified under biochar schemes. Their charcoal granules also pass the chemical standard. These charcoal fines are certified biochar.

There are claims that charcoals often contain tars, PAHs. Well yes, some will (as do some biochars that fail the tests!). Most ‘tar’ issues are related to BBQ briquettes made from coal dust.

Summary

You now have the knowledge that charcoal and biochar can be both the same and not the same, ie it depends and what it depends on. A good shorthand: look for and buy ‘certified biochar’ – that way you know it is made sustainably and meets the chemical purity as stated.

- What Is Biochar?

👉 Quick answer

Biochar is a carbon‑rich material made by heating plant or organic biomass in low oxygen. It’s long‑lasting, climate‑positive, and used in many industries. But biochar is not one product — different feedstocks and production methods create very different materials.

Biochar can be used in soil, construction, filtration, plastics/composites, and carbon‑removal markets. Its benefits depend on how it’s made, prepared, and applied.

If you want the full picture — including production technologies, global supply, activated carbon vs biochar, and the major emerging markets — continue below.

👉 What biochar is

Biochar is biomass that has been heated without oxygen (a process called pyrolysis). This turns it into a stable carbon material that:

- Stores carbon for centuries.

- Has pores and surfaces that interact with nutrients, microbes, and chemicals.

- Behaves differently depending on feedstock, temperature, and particle size.

Think of it as engineered charcoal, but produced cleanly, sustainably, and for specific industrial uses.

👉 Why biochar matters today

Biochar sits at the crossroads of three global priorities:

- Climate – it locks away carbon (Puro, Verra, EU carbon‑removal schemes).

- Soil Health – it is stable soil carbon, helping improve soil health.

- Materials innovation – it replaces sand, fillers, perlite, activated carbon, and more.

Industries are adopting biochar because it provides functional performance AND carbon savings.

🔬 Technical deep‑dive

1. Biochar is not one material

Different biochars vary because of:

- Feedstock (wood, coir, straw, husks, digestate, manures, agri‑waste).

- Pyrolysis technology (fast gasification, medium pyrolysis, torrefaction).

- Temperature (200–1,000°C).

- Particle size (powder → 20 mm granules).

Each combination creates different chemistry, porosity, ash content, and use‑cases.

2. Feedstocks and why they matter

- Wood / forestry → clean, low ash, high stability. Best for soil, composites.

- Coir / husks / fibres → abundant in Asia; becoming major horticultural input.

- Straw / agri residues → high ash; strong for bricks, tarmac, concrete.

- Manures / digestate fibre → nutrient‑rich but variable; niche industrial uses.

- Food waste → inconsistent; mostly energy charcoal, not premium biochar.

Feedstock determines suitability for:

- Soil amendments

- Built‑environment materials

- Filtration

- Carbon‑removal markets

3. Production technologies (the three big routes)

A) Fast gasification (800–1,000°C)

- Very high temperature

- Low‑yield, high‑purity carbon

- Approaches activated‑carbon properties

- Used when heat/power is the primary goal

B) Medium pyrolysis (400–650°C)

- Most common for soil, composites, and construction

- Balanced porosity and carbon yield

C) Torrefaction (200–350°C)

- Low‑temperature chars (more often called “pre‑char, biocoal, or torrefied biomass) are used as a fuel to replace fossil fuel coal. (Technical note: many torrefied chars may well meet the biochar chemical certification standard….But: they do not qualify as certified biochar, as burning returns CO2 back to the atmosphere, so they are outside the sustainability criteria for ‘certified biochars. Most marketing materials distinguish, but for completeness, we list them out.

- Not suitable for stable carbon storage or high‑performance uses

Temperature controls:

- Carbon stability

- BET surface area

- Pore type (micro/meso/macro)

- Volatile content

- End‑use suitability

4. Particle size formats

Particle format influences not just handling but function:

- Powders (2–500 µm): coatings, fillers, composites; not ideal in soil.

- 0.5–2 mm fines: best for soil aggregation and microbial colonisation.

- 2–8 mm granules: used in concrete, filtration, structured soils.

- 10–20 mm chunks: low interaction; niche uses.

5. Where biochar is used (the four big markets)

A) Soil & land management

- Improves structure, WHC, aeration, aggregation.

- Boosts microbial activity.

- Stabilises humus.

- Provides long‑term carbon storage.

See full soil-fit biochar article at Healthy Soil.uk

B) Built environment (tarmac, concrete, bricks)

- Reduces weight of concrete.

- Improves insulation.

- Lowers embodied carbon.

- Partial sand/cement replacement.

C) Filtration & purification

- Good for bulk contaminant reduction.

- Works for phosphorus, metals, and some organics.

- Often used as a pre‑filter, it is growing in demand as a sustainable replacement for activated carbon.

- New biofiltration markets using special properties for filtering out soil runoff nutrients and creating a soil amendment. See: BiocharFilters.co.uk.

D) Polymers, composites, resins, plastics

- Acts as a carbon‑negative filler.

- Improves fire resistance and mechanical strength.

- Growing use in 3D printing and foams.

6. Biochar vs activated carbon (easy confusion)

They look similar — but functionally, worlds apart.

Feature Biochar Activated Carbon Source Biomass Fossil or biomass Processing 350–650°C 800–1,200°C + activation BET surface 200–450 m²/g 800–1,200+ m²/g Pores Meso/macro Deep micropores Best for Soil, composites, bulk filtration Fine filtration, VOC removal Biochar cannot replace activated carbon in high‑performance filters — see BiocharFilters project page.

7. Biochar vs Charcoal

Although the words are often used interchangeably, charcoal and biochar are not always the same thing.

A good shorthand: all biochar is a type of charcoal, but not all charcoal is safe or certified to be biochar. If you want to know the details, jump over to our FAQ biochar Vs Charcoal

8. Carbon‑removal markets (Puro, Verra, EU CRCF)

Biochar is now recognised as an engineered carbon‑removal pathway:

- Puro.Earth (EBC‑certified removals)

- Verra VM0044 (biochar land application)

- EU CRCF (upcoming certification framework)

Why these matter:

- Biochar carbon is stable for centuries

- Removal is measurable and auditable

- Hard‑to‑abate industries (cement, bricks, steel, aviation) need certified removals

Carbon credits often underpin the commercial viability of large biochar plants.

9. Who will produce biochar — and where?

Asia (India, Sri Lanka, SE Asia)

- Massive coir and agri‑residue streams

- Likely dominance in horticultural and substrate biochars

Europe & UK

- Forestry brash, chip, hedgerow biomass

- Strong policy drive for domestic removals

- Growth expected in the construction and filtration sectors

Americas

- Soil, carbon credits, and activated‑carbon substitution markets

- Fast growth in regenerative agriculture

Hemp and emerging fibres

- High‑yield, low‑ash feedstock

- Ideal for composites and technical chars

10. Pitfalls, hype, and what to avoid

- Biochar ≠ activated carbon

- Low‑temperature chars behave like fuel, not stable carbon

- Powders behave differently than granules

- Uncertified charcoals may contain tars/PAHs

- Many business models rely heavily on carbon credits

Summary

Biochar is a family of engineered carbon materials with diverse behaviours and applications. It spans soil improvement, construction, filtration, composites, and carbon removal. The sector is expanding rapidly, with Asia leading horticultural production and Europe leading engineered removals.

- Where our interest in biochar filtration began (2015)

In 2015, we ran a simple experiment that unexpectedly kick-started our interest in using biochar as a water-filtration medium. At the time, we were asking a basic question: could wood-based biochar rival or even replace activated carbon in aquariums?

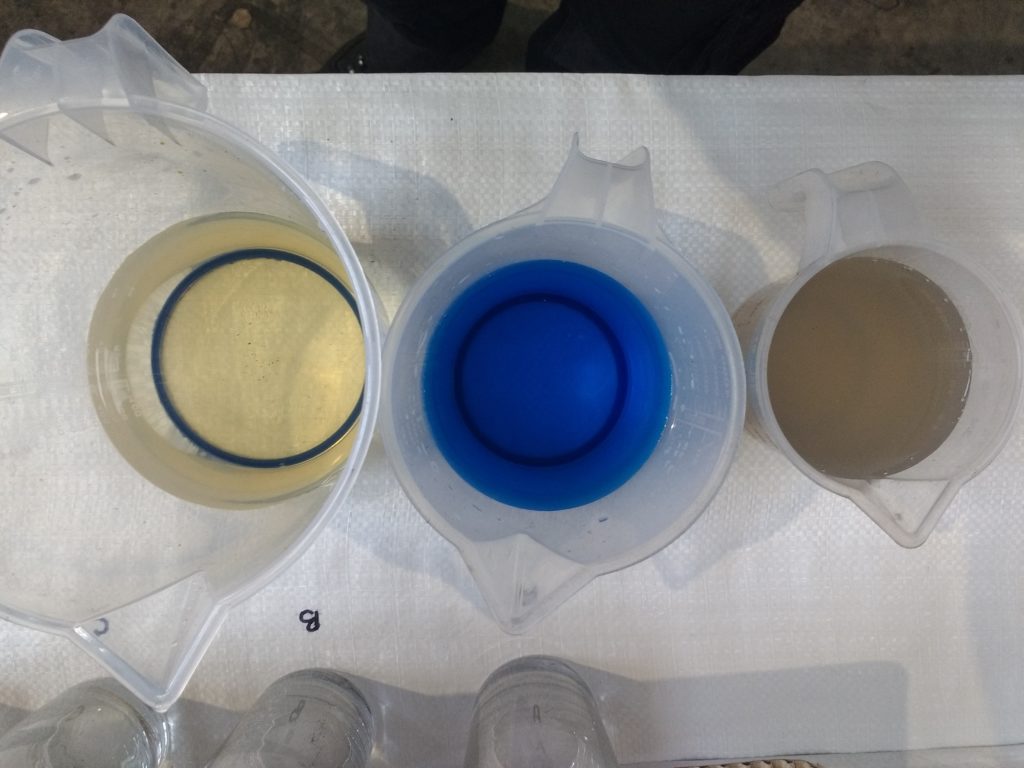

Using 500 ml plastic bottles as mini test columns, we filled each with a known weight of carbon and passed dyed water through them — iodine for small molecules, methylene blue for medium ones, and a compost-derived DOM solution to mimic the yellowing that develops in tanks. Despite the simplicity of the setup, the results were revealing. Performance varied widely between products, and once the test was corrected for equal carbon mass, the wood-based biochar granules held their own against commercial pellets.

More importantly, we noticed early signs that porous wood char might also support beneficial microbial activity — hinting at a combined chemical-and-biological “biofilter” mode long before we explored it formally.

That modest bottle test became the seed for everything that followed in our biochar-filter journey.